Increasing Learner Motivation through Practice and Feedback in eLearning Courses

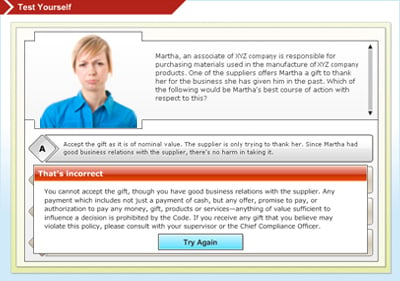

Ever been put off by feedback for a practice question in an online course that was just an unhelpful “That’s incorrect. The correct answer is…”, without any attempt at explaining why the answer was incorrect?

I was thinking of why we do what we do as instructional designers when it comes to providing practice and feedback. Here are a few questions we can ask ourselves when designing practice and feedback.

- Why do we give our learners practice questions (non-scored, and not part of the formal assessment)? Is it just to test them? Give them a welcome break from the instruction? Or give them the opportunity to practice what they have learnt? Or use the feedback to their answers as a teaching tool?

- Why do we spread out our practice questions over regular intervals (typically at the end of manageable chunks of learning)? What are we hoping to achieve through this? How can we apply the strategy of increasing their motivation by giving them a chance to succeed? By first appreciating it when they get something right and then focusing on what they got wrong? Are there any other ways to let the learner succeed? How important do you think this is for learner motivation?

- Is our feedback directed at the learner (minus any comments implying a personal deficiency), rather than focusing on the task being performed. Think of the difference between “You are wrong” and “In this step, you added the two amounts instead of subtracting them”, which brings us to the topic of diagnostic feedback in the bullet below.

- Ever thought of the powerful impact of diagnostic feedback for tasks in terms of appreciating progress learners have made rather than pointing out how far they still need to go? Think of how partial feedback can be powerful in helping learners who may not have got the answer 100% correct. When they get feedback on the method they used at arriving at an answer rather than on the answer itself, it certainly gives them a very strong reason to get it right. This also helps them take mid-course correction. It’s frustrating as learners to be told we are wrong and then not have any information on where and how we went wrong.

- How can we help out learners through the process of arriving at the correct answer? Think of hints that we can provide or reference materials learners can be directed to for helping them solve a problem correctly (For instance: refer to this job aid so that you don’t skip any important steps while solving the problem.)You could also improve their motivation by letting them see how the course gives them the opportunity to make mistakes in a risk-free environment.

- Why do we model the desired performance? And how we do it? Maybe through videos of optimal performance for a given task? Think of a scenario in a sales training where the characters in a role play can be used to both model ideal performance and the not-so-ideal performance so that learners can think of both how to succeed and how not to succeed.

Robert Mager‘s talks about self-efficacy in his book How to turn learners on…without turning them off. He defines it as the “judgments people make about their abilities to execute particular courses of action-about their ability to do specific things. It isn’t about the skills people have, but about the judgments people make about what they can do with those skills.” So what’s self-efficacy got to do with instructional design? If we design our courses in such a way that we strengthen our learners’ self-efficacy, they are more likely to hang in there and not give up at the first sign of failure. Course designers can help mirror on-the-job conditions while giving learners somedegree of support and reassurance as they go through the course.